Oral presentations have gained in popularity with the Government over the past 5 years. Why has there been an increase in demand for these types of proposals? What does the Government achieve through having your personnel present, either in person or virtually, to the evaluators instead of submitting a written document? Through my experience, there are three things the Government is looking to see from your team when they request oral presentations. While not part of the defined evaluation criteria, the impression these three things leave with the evaluation panel can mean the difference between success and failure.

Reason 1: Are You Technically Capable? This is the basic table stakes of any proposal – can your team execute the work required? In a written proposal, firms can use partners or consultants to put together a clear, compelling narrative. However, in an oral presentation, there is little room to hide. Your presenters need to be able to clearly and convincingly speak to the complex technical factors. It is easy to spot when a presenter did not write their own content, and they are not experts in the subject matter. In addition, when the opportunity to ask questions arises, the Government will quickly see the inexperience and lack of knowledge of the presenter. The technical capabilities of the presenting team and the offeror are important. However, reasons two and three are significantly more important and, as such, provide a clear way for your team to differentiate yourselves.

Reason 1: Are You Technically Capable? This is the basic table stakes of any proposal – can your team execute the work required? In a written proposal, firms can use partners or consultants to put together a clear, compelling narrative. However, in an oral presentation, there is little room to hide. Your presenters need to be able to clearly and convincingly speak to the complex technical factors. It is easy to spot when a presenter did not write their own content, and they are not experts in the subject matter. In addition, when the opportunity to ask questions arises, the Government will quickly see the inexperience and lack of knowledge of the presenter. The technical capabilities of the presenting team and the offeror are important. However, reasons two and three are significantly more important and, as such, provide a clear way for your team to differentiate yourselves.

Reason Two: Can Your Team Work Together? When asking for an oral presentation, the Government is doing a group interview. The instructions often mandate the key personnel identified in the solicitation deliver the presentation. These individuals are the ones the client sees as the core of your delivery team. As such, they want to know if your team can work well together, or if they are a group of individuals. Did you put together a cohesive team that can execute and handle the day-to-day challenges of the program collectively, or are they a bunch of people you threw together based just on the personnel requirements?

For me, this is a great opportunity to illustrate the chemistry your team has. There are many ways we can demonstrate this cohesiveness. The first opportunity happens before the presentation begins. I tell my teams they are being judged from the second they walk into the building until they leave. Therefore, any chance you have to show team chemistry and understanding is a positive. The small talk you have walking into the presentation room may seem insignificant. However, when you ask about Jon’s daughter’s softball game or Jane’s nephew’s piano recital, it shows you have pre-existing relationships and connections. To achieve this, I try to get my teams together outside of the practice room. I have them all go to lunch or out for a drink together. I have them sit near people they do not know. People begin to chat and get to know each other in these situations. It builds chemistry and cohesion amongst your presenters and helps develop them into a singular team.

Secondly, building cross-talk into the presentation helps show you know your teammates and what they bring to the table. Whenever possible, reference other parts of the presentation and the individual responsible for it. For example, “later on, Steve is going to talk in detail about our security approach” or “earlier, Sally introduced our approach to security. Let me provide you with further detail now.” This reference shows your team has understanding of the rest of the presentation and the roles of the team within it.

Reason Three: Can They Work With You? This might be the most important hidden question the Government is asking during your presentation. Are you, both individually and collectively, someone they want to work with? Just like a resume can present skills but an interview is required to see if someone is a good fit, a written proposal can speak to capabilities but oral presentations bring out the character of your team and whether or not they would be a good fit for the environment and style of the client.

Reason Three: Can They Work With You? This might be the most important hidden question the Government is asking during your presentation. Are you, both individually and collectively, someone they want to work with? Just like a resume can present skills but an interview is required to see if someone is a good fit, a written proposal can speak to capabilities but oral presentations bring out the character of your team and whether or not they would be a good fit for the environment and style of the client.

My number one tip here is to be authentic. I work with my teams to not memorize scripts or dramatically change their speaking styles. I work to maximize their strengths and then mitigate any dramatic weaknesses (speaking too quickly or too quietly, for instance). This allows the real person to shine through and for the evaluators to clearly see you are someone they want to work with.

Conclusion. Oral presentation skills are increasingly becoming a must have for every Government contractor. By being aware of what the Government is looking for that is not explicitly in the evaluation criteria, we can prepare more thoroughly for the presentation and show the Government we are the team they are looking for.

Are you in need of high-quality, focused orals coaching? Reach out to our team today – click here for more information.

The first clue to making our proposal focused on our clients is to use their language. This applies throughout your proposal. There are standard definitions in the industry for corporate experience (what you have done) and past performance (how well you have done it). However, that distinction is not always clear to everyone. Sometimes, clients ask for “past performance” when they actually mean corporate experience. In these cases, do not fix their terminology – use their terminology.

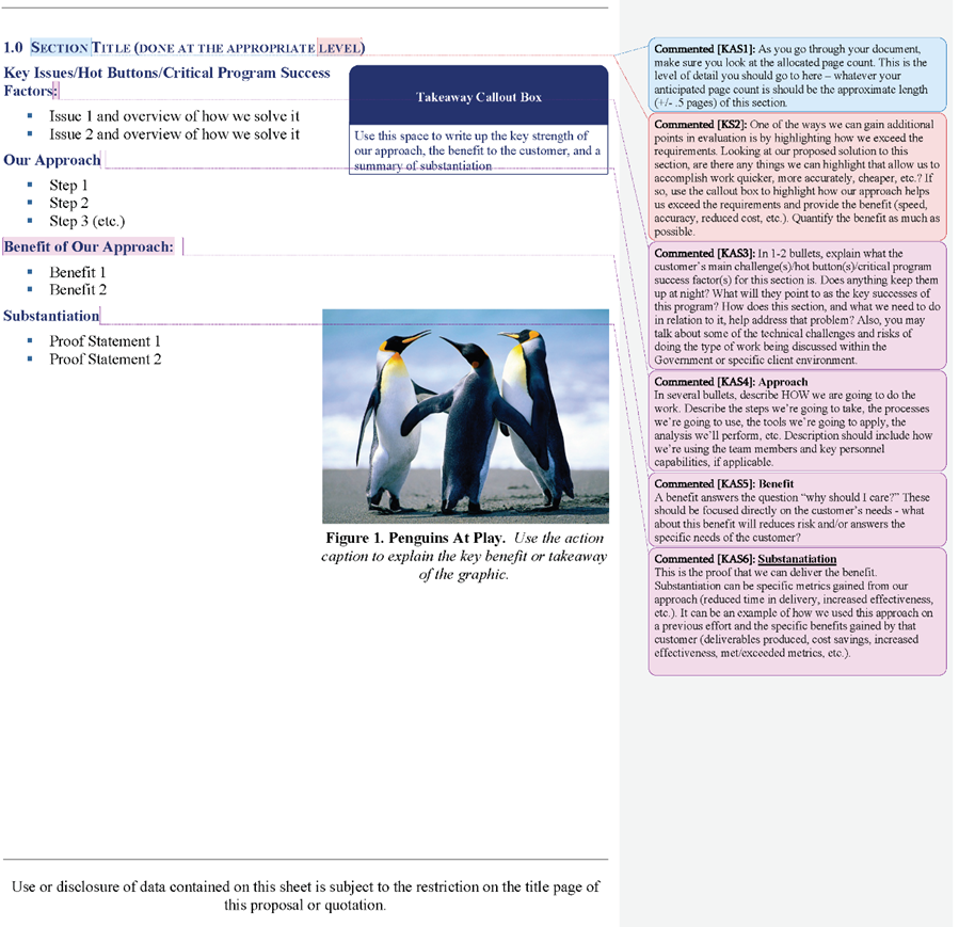

The first clue to making our proposal focused on our clients is to use their language. This applies throughout your proposal. There are standard definitions in the industry for corporate experience (what you have done) and past performance (how well you have done it). However, that distinction is not always clear to everyone. Sometimes, clients ask for “past performance” when they actually mean corporate experience. In these cases, do not fix their terminology – use their terminology. Too often, people rely heavily on prior write-ups when putting together your corporate experience examples. When developing your submission, however, taking boilerplate and putting it in the proper format is not an option. Just copying and pasting in a generic list of work performed and achievements does not speak to the individual needs of the client. Therefore, besides just using the client’s terminology, you need to select the portion(s) of the work you are currently doing that are clearly relevant to the solicitation. I have my teams talk in broad strokes in the opening paragraph with a two to three line summary of the overarching contract. Then, I have them specifically state how it is relevant in terms of the evaluation criteria and work expected. For the former, often in Federal Government bids we are asked to write to size, scope, and complexity. For the latter, we want to show alignment to the work required (the performance work statement/statement of work). In either case, a nice summary table can work wonders. Include all the PWS/SOW requirements and allow for a checkbox or a meatball chart to show that alignment.

Too often, people rely heavily on prior write-ups when putting together your corporate experience examples. When developing your submission, however, taking boilerplate and putting it in the proper format is not an option. Just copying and pasting in a generic list of work performed and achievements does not speak to the individual needs of the client. Therefore, besides just using the client’s terminology, you need to select the portion(s) of the work you are currently doing that are clearly relevant to the solicitation. I have my teams talk in broad strokes in the opening paragraph with a two to three line summary of the overarching contract. Then, I have them specifically state how it is relevant in terms of the evaluation criteria and work expected. For the former, often in Federal Government bids we are asked to write to size, scope, and complexity. For the latter, we want to show alignment to the work required (the performance work statement/statement of work). In either case, a nice summary table can work wonders. Include all the PWS/SOW requirements and allow for a checkbox or a meatball chart to show that alignment. As hard as our teams work to execute on all of our contracts, nothing is perfect. Things go wrong. Sometimes it’s something minor. Other times, it is a serious issue that results in escalation, cure notices, and egg on our face.

As hard as our teams work to execute on all of our contracts, nothing is perfect. Things go wrong. Sometimes it’s something minor. Other times, it is a serious issue that results in escalation, cure notices, and egg on our face.